The Coming Economic Nightmare

Trump’s tariffs could cause stagflation for the first time in decades. It may go on for a long, long time.

I remember the little stickers on restaurant menus.

In the 1970s, it cost much more to print a menu than it does today. Restaurants did not change them often. When prices rose, they’d retain their old menu—but affix little stickers with the new, handwritten prices atop the previous ones. When prices rose especially rapidly, the stickers accumulated in stubby columns rising up from the menu. A bored child might scratch off all the stickers with a fingernail—and, like a young archaeologist, reveal a lost world.

The term that came into use to describe the era was stagflation: stagnation plus inflation. Until recently, it seemed a relic of the disco era, but the economic chaos of Donald Trump’s second presidency has resurfaced the old word. Stock markets are warning of a recession. Bond markets are anticipating inflation. Perhaps one market is wrong, or the other, or both. More likely, they portend the return of a half-forgotten nightmare.

From 1969 to 1982—just 13 years—the United States suffered four recessions. Three were severe. Two were both severe and protracted. Recoveries were comparatively feeble. Even during the recessions, prices kept rising.

The era’s economic turmoil unnerved Americans. Mass-market best sellers such as The Late Great Planet Earth prophesied the imminent end of the world in a biblical apocalypse. Americans absorbed a secular version of the end-of-the-world obsession from books such as The Limits to Growth, which claimed that humankind was overconsuming almost every natural resource and had no choice but to strictly ration the pitiful remains.

In his famous 1979 speech, which came to be known as the “malaise” address, President Jimmy Carter warned: “The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America.” Conversation everywhere, the historian Theodore White wrote, was “stained and drenched in money talk, by what it cost to live or what it cost to enjoy life.” Especially outside the upper classes, people “winced and ached. Some mysterious power was hollowing their hopes and dreams, their plans for a house or their children’s college education.” What could they do? How could they recover? “Faith in one’s own planning was dissolving—all across the nation,” White wrote. “The bedrock was heaving.”

The unease destabilized American politics. Carter lost his reelection bid in 1980; his predecessor, Gerald Ford, likewise had been voted out in 1976. Richard Nixon might well have survived Watergate (as Trump has survived his many scandals) had the investigation not unfolded during the most miserable American economy since the Great Depression. In House elections, the party of the president suffered unusually heavy losses: 49 seats in 1974; 26 in 1982.

[David Frum: Sorry, Richard Nixon]

Finally, the stagflation was choked to an end in the fourth and climactic recession of 1981–82. In late 1983 and ’84, the U.S. economy rebounded powerfully—and this time, the inflation did not return. Stagflation vanished into history. The economy has seen its share of tumult in the 21st century: the Great Recession, a recent bout of high inflation. But it’s been a very long time since Americans have felt recession and inflation at once.

In January, President Trump inherited an economy that was growing strongly. Unemployment was low. Inflation had been restrained below 3 percent. If the new Trump administration had just left well enough alone, his second presidency could have coasted to economic success.

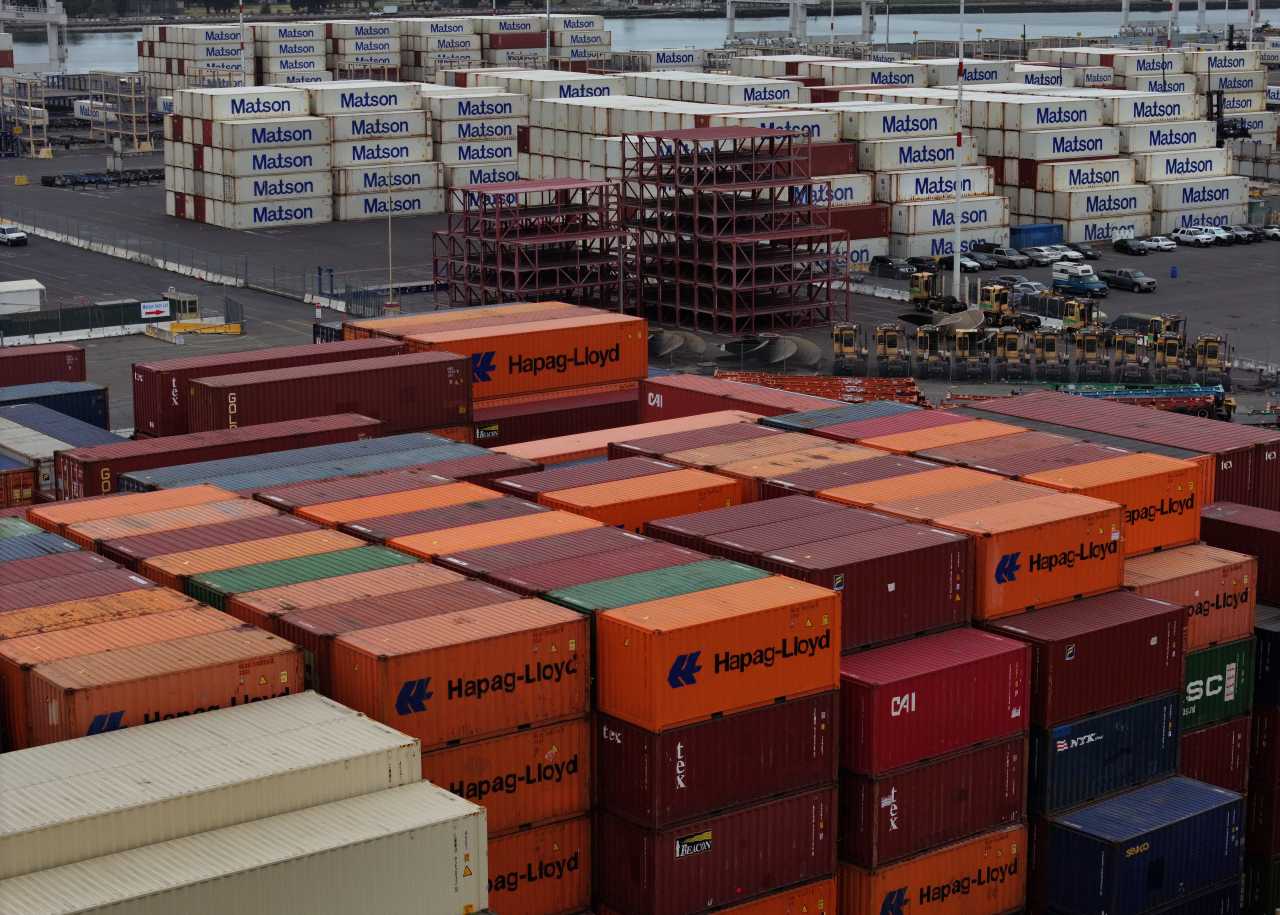

Instead, Trump single-handedly plunged the economy into chaos. In the ’70s, the economy was disrupted because the price of oil surged, a result of the major oil producers’ coordinated restriction of supply. Trump’s tariffs are like a hundred self-inflicted oil shocks, all arriving at the same time. Unless Trump changes course immediately, everything will soon cost more, possibly a lot more: groceries and automobiles, industrial magnets and tableware, mobile phones and children’s shoes.

Trump and his surrogates promise that from this upheaval will emerge a new era of American industry. Tariffs on foreign products will induce investors to build factories in America. Even if this promise came true, the result would still be a bad bargain. Tariff-sheltered industries tend to produce inferior goods at higher prices, and have little incentive to do otherwise. If the goods were competitive, after all, no tariff would be needed or wanted.

But Trump’s tariffs will not induce much factory-building. Who’d invest in a factory to produce made-in-America goods at higher-in-America prices unless assured that foreign competition would be excluded for a long time, if not forever? Trump’s tariffs are here today, gone tomorrow, maybe back the day after that, maybe not. On some days, Trump vows to keep his tariffs in place permanently; on others, he speculates about trading them away for hypothetical future deals. Disadvantages and uncertainties compound: The tariff-protected American car of the future Trump fancies, for instance, will be assembled from steel, glass, plastic, fabric, and electronics, all of them tariffed too: at 10 or 20 or 125 percent, or whatever other random number pops up on Trump’s Truth Social feed that morning.

No American business—no business that serves the American market—will commit to any capital expenditure under these conditions. If Trump’s tariffs last for any length of time, the result will be a vast disinvestment instead. The worst of the pain may not be felt immediately. Trump advertised the tariffs many weeks in advance, opening an opportunity for businesses to stockpile inventories. Sooner or later, however, those stockpiles will dwindle. Consumers will face higher prices or outright shortages. Businesses will suffer diminished demand. Workers will be laid off.

The only early hope is that the president who set the maelstrom going will panic and try to stop the wreckage. But he seems just as likely, perhaps more so, to make that damage worse. The presidents of the ’70s desperately gambled with extreme measures of state control to stop inflation without aggravating unemployment. Nixon imposed wage and price freezes in 1971 and ’73; in 1977, Carter proposed an elaborate scheme of controls, taxes, and subsidies across the energy sector. These experiments sometimes delivered a short bump in the polls—but quickly presented their authors with a dilemma: State control begets economic distortions, which demand more state control. Either the would-be controller advances toward ever greater political command of the economy—or the would-be controller is quickly forced to retreat in failure and embarrassment.

Donald Trump has no grasp of history. The people around him are afraid to teach it to him. So Trump’s trade war could well lead him, as the economy sinks, to ever more interventionism of his own: subsidies and tariff exemptions for favored companies; payouts to farmers and other constituencies; political warfare against the independence of the Federal Reserve.

The most dangerous temptation that Trump may face is to impose some form of capital controls to stop investors from dumping dollar assets. Trump’s trade war has driven a sell-off of U.S. Treasury bonds, which raised interest rates in the United States. Regimes moving toward protectionism sometimes try to block investors from rushing to the exits. The United States has more capacity than most to try such measures. Among their many costs, they dissuade investors from ever trusting your country again.

The grim fact about stagflation is that—once stumbled into—it is very hard to escape. Raise interest rates to curb the inflation, and the stagnation gets worse. Rev the economy to overcome stagnation, and the inflation gets worse. Policy makers find themselves in the predicament of a motorist trying to execute a three-point turn in a too-narrow roadway: They can never back up or advance far enough to make any progress.

The whole incomprehensible system that Trump is building—haphazard, anti-market, punishing to consumers and businesses alike—will have to be rewritten by the next president, or maybe junked by the next Congress if it has the votes to override Trump’s veto and reclaim the legislature’s constitutional power over tariffs and trade.

But whenever the government gets serious about repair and recovery, Americans will face more difficulties emerging from their tariff-caused stagflation than their oil-shocked predecessors did half a century ago. Impose a tariff on bananas: The price will rise; demand will drop. As the drop in demand is felt, investment will decline in the boats and warehouses that bring the bananas to market. Fewer banana trees will be planted; the people who work on banana plantations will find other jobs; the capital committed to banana production will be redeployed.

Lift the tariff on bananas, and the process will not immediately reverse. The memory of the arbitrary tariff will shape behavior for some time afterward. Recommitting the capital, rehiring workers, replanting trees, reinvesting in warehouses and boats—none of that will be instant. Banana prices may remain elevated in the tariff-imposing country for some while after it mends its ways. And as it goes with individual commodities, so it goes with the entire global system of production and trade.

The economic crisis of 2025 started in the mind of one man, but Trump’s tariffs are dislocating planet-wide networks of trade. The dislocation has already sliced trillions of dollars from the value of U.S. corporations. Even if Trump ceased his trade actions tomorrow, the possibility that he could resume them would depress the value of almost every U.S. and international company.

Foreign governments, faced with Trump’s bullying, have retaliated in ways that dislocate trade further. They may or may not end their retaliation when Trump has had enough. By then, many of them will have formed new trading arrangements that bypass the United States.

Trump will demand cheaper money from the Federal Reserve. He has already threatened to fire the Fed chairman, Jerome Powell, for recently declining to lower interest rates. Potential politicization of the Fed will frighten bondholders and push interest rates up—depressing the value of stocks, discouraging new investment, and raising the cost of mortgages, auto loans, and student debt.

Ultimately, the end of the crisis will depend on the actions of hundreds of millions of people across dozens of trading nations. Only if and when they recover their trust in the United States will the U.S. and world economies fully recover from the breach of trust Trump has created. How long will it take? No one knows.

As a businessman, Trump was notorious for operating in bad faith. He has been accused of deceiving customers, employees, investors, and creditors. Before he pivoted to politics, his bank of choice was one known for its relationship with Russian oligarchs and alleged money launderers. He repeatedly drove his properties into bankruptcy, leaving creditors, investors, and employees to bear the costs of his failure.

As a politician, Trump vowed to “make America great again” with the same predatory methods he used in business. He does not appear to believe in mutually beneficial transactions. The only way he feels confident that he prevailed is if the other party suffers. His plan for enriching America was predicated on dominating and wronging others. Plans like that seldom work even at the start, and never work for long.

Good faith is the beginning of success for nations as well as individuals. Trump’s bad faith and poor choices once ruined only those who made the voluntary personal or corporate decision to do business with him. But no one can choose to sit out Trump’s trade war. The casualties are already accumulating.

This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “That ’70s Feeling.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?